The History of the 19th Amendment

September 23, 2020

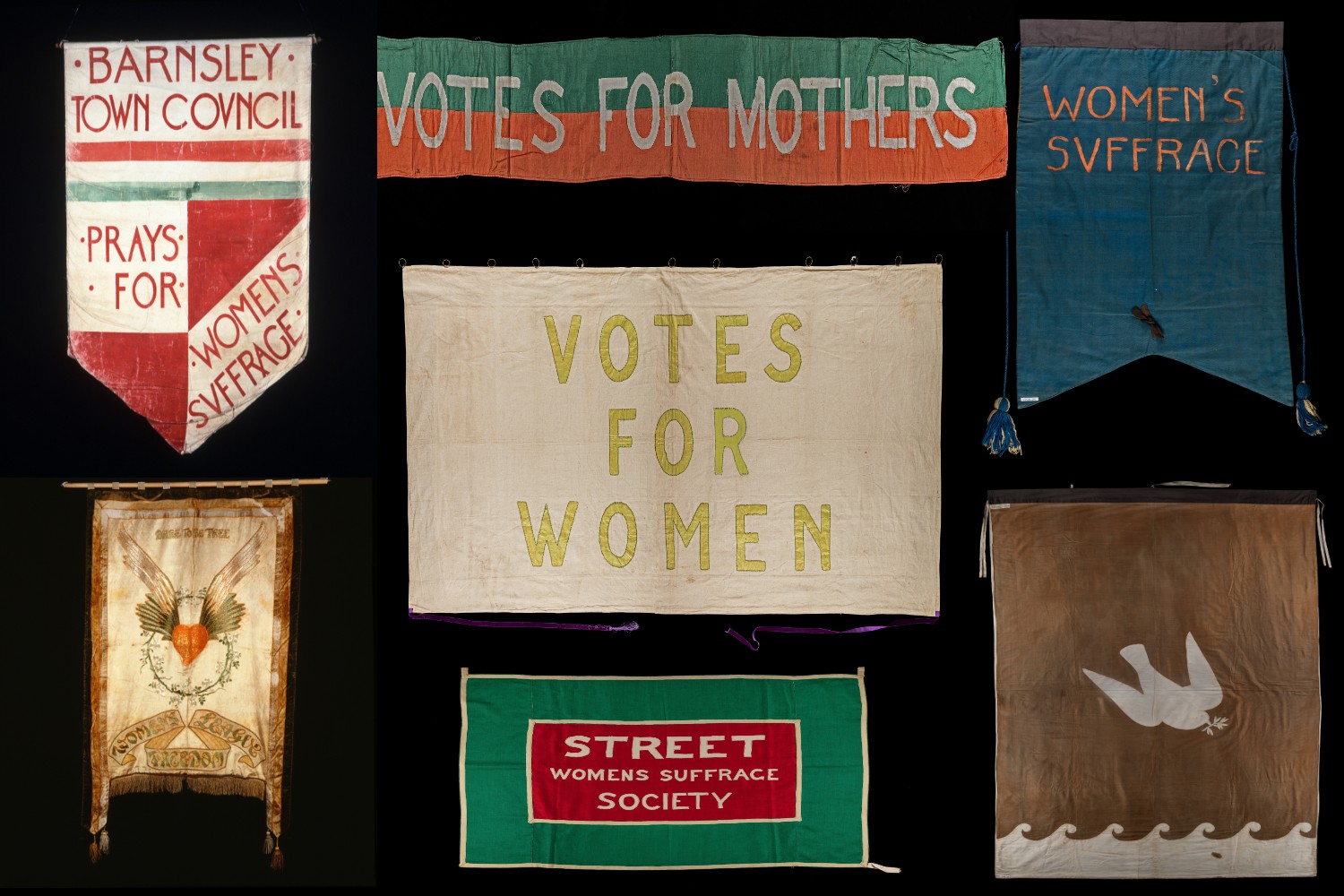

100 years ago on Aug. 18, the nineteenth amendment was ratified, allowing women across the nation the right to vote. What you may not know is that the fight for this right began many years before 1920.

In the 1820s and 1830s, most states had granted all white men the right to vote, regardless of how much money or property they had. Meanwhile, many reform groups had spread across the U.S., and many were led by women.

In 1840, Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Lucretia Mott, two women who crossed the Atlantic to attend the World Anti-Slavery Convention, were excluded from the main floor, as were all the women present, and forced to listen from the gallery. They grew close over their common plight, and, thus, the U.S. women’s rights movement was born.

Eight years later in 1848, Jane Hunt, a wealthy Quaker, invited Stanton, Mott, Mary Ann McClintock, and her sister Martha Wright over for tea, where they brainstormed their first act. Later that month, Stanton and Mott held a women’s rights conference at Seneca Falls, New York. Two hundred women came to the first day of the conference, and the next day, more than 30 men joined at the women’s invitation, including Frederick Douglass — an escaped slave and activist.

During the convention, Stanton read aloud the “The Declaration of Sentiments: Women’s Grievances Against Men,” which is modeled after the “Declaration of Independence.” The document listed existing injustices against women in the U.S. and called for women to be considered citizens and granted equal civil, economic, and political rights with men.

Ally Smith (’23), says “I think the 19th amendment was the first step in making women equal.”

It was originally signed by 68 women and 32 men, but many withdrew their signatures due to criticism and backlash after the document became public.

“We hold these truths to be self-evident: that all men and women are created equal; that they are endowed by their Creator with certain inalienable rights, that among these are life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness,” Stanton said.

Douglass took the Declaration to a New York print shop and published it in his newspaper, “The North Star.” The printing made is the oldest known copy of the document. To this day, the original “Declaration of Sentiments and Grievances” has not been found.

In September of 2018, at the Grace Hopper Celebration of Women in Computing, White House Chief Technology Officer Megan Smith launched an official search for the Declaration.

“We need to expand who is included in our well known story. ‘The Declaration of Sentiments can help us tell that story,’” said Smith.

When the Civil War began, the movement lost momentum, but after the war ended, the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments raised the questions of suffrage and citizenship for women once again. The Fourteenth Amendment was ratified in 1868 and extended the constitution to “all citizens,” citizens meaning all white men. The Fifteenth amendment, ratified in 1870, guaranteed black men the right to vote.

"Any great change must expect opposition, because it shakes the very foundation of privilege." – #LucretiaMott https://t.co/x1zaZNxKWN

— Miss Representation (@RepresentPledge) August 26, 2016

In 1890, the National Woman Suffrage Association, founded by Stanton and Susan B. Anthony, and the American Woman Suffrage Association merged to form the National American Woman Suffrage Association, with the first president being Stanton. At that time, suffragists were no longer arguing that women deserved the same rights as men because they were equal, but rather because they were different from men. 30 years later, women were allowed the right to vote, and on Nov. 2, 1920, more than 8 million American women voted in elections for the first time. Grace Jaye, (’24), says “I’m really glad that it was passed. I’m glad we have rights. I think everyone should have rights.”

Sarah Aschenbrenner (’23), says “I’m really glad that women got the right to vote because we can contribute to society and … express our opinions.” Many people worked hard for our right to vote as women, so now we must use that right. Election day is Nov. 3.