Fault in the Grand Jury System in Cases Involving Police is Exposed in the Wake of Breonna Taylor’s Death (EDITORIAL)

October 2, 2020

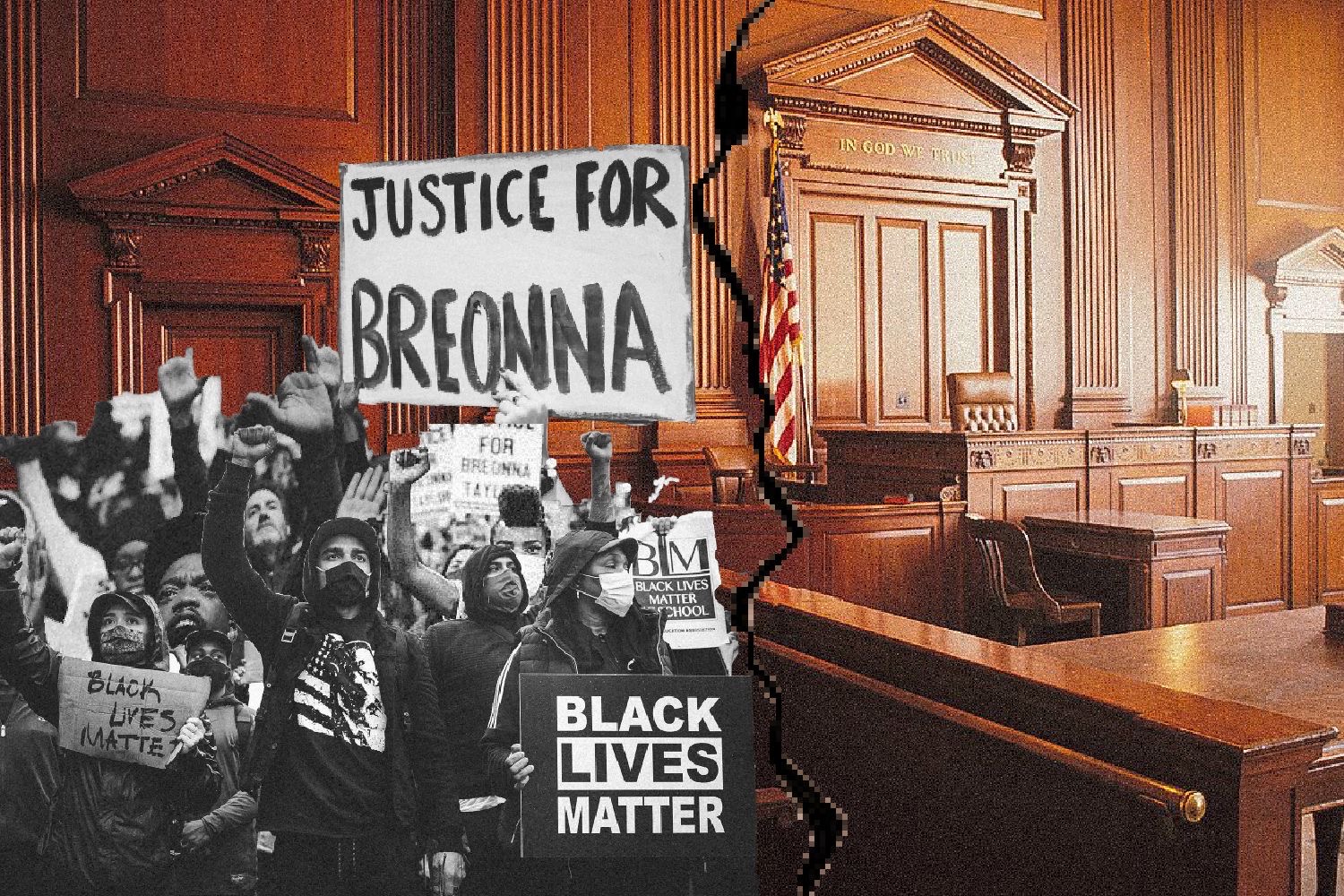

Asleep in her bed on March 13, 2020, 26 year-old Emergency Medical Technician Breonna Taylor was shot eight times when police raided her apartment in Louisville, Kentucky. She died.

And after a Kentucky grand jury hearing on Wednesday, Sep. 23, only one of the three officers involved was indicted — Brett Hankison —, yet not for Taylor’s death, but on three accounts of wanton endangerment of a neighboring apartment where bullets reached.

Grace Jaye (’24) said, “I think it [the ruling] was such a shame because the police officer who killed her should go to jail.”

We've been saying "Say Her Name" for six months… and #BreonnaTaylor's name was NEVER mentioned in yesterday's indictment…

— Ben Crump (@AttorneyCrump) September 24, 2020

Many took to the streets protesting for all officers involved to be arrested while chanting “say her name.” The Say Her Name campaign, created in 2014, aims to bring more national attention to cases like Taylor’s. Although NPR reports that “men make up the vast majority of people shot and killed by police,” there is a lack of coverage given to crimes against Black women by police; names such as Michelle Cusseaux and Kayla Moore are less familiar than those of George Floyd or Eric Garner. Taylor’s case has not only brought attention to the disproportion of coverage regarding police brutality towards Black women, but also highlighted possible injustices in grand jury hearings in cases involving police.

For instance, this is not the first time a case involving law enforcement has not been subject to an indictment. More specifically, there seems to be a trend in which cases involving police and Black men and women fail to receive an indictment.

Daniel Pantaleo, who put 43 year-old Garner in a choke hold — and subsequently died — in 2014, was not indicted.

Darren Wilson, who shot and killed 18 year-old Micheal Brown in 2014, was not indicted.

Timothy Loehmann, who shot and killed 12 year-old Tamir Rice in 2015, was not indicted.

It is extremely rare for a police officer to be charged with an on-duty manslaughter or murder and even fewer are convicted. About 1,000 people are killed by police each year in the U.S., but since 2005, only 121 officers have been charged with murder or manslaughter — 44 of those were convicted out of the 95 concluded cases.

Overall, however, indictments are easy to come. For example, from October 2009 through September 2010 “U.S. prosecutors pursued 193,000 cases and prosecuted 162,350. Of the more than 30,000 they didn’t prosecute, 11 cases were because a grand jury did not return an indictment,” according to The Washington Post.

This begs the question: Is there a fault in the grand jury system?

Michael Brown: No Indictment

Eric Garner: No Indictment

Sandra Bland: No Indictment

Tamir Rice: No IndictmentTHE SYSTEM IS BROKEN.

— Jason Pollock (@Jason_Pollock) December 29, 2015

According to the Offices of the United States Attorneys, the grand jury process is as follows: “For potential felony charges,” the prosecutor presents the case to a group of impartial individuals that comprise the grand jury — about 16 to 23 people. Then, based on the evidence given and possible witnesses who testify, the jury decides whether or not there is enough evidence to indict the individual; “At least 12 must concur in order to issue an indictment.” All this is done in secrecy, and it is also important to note that states differ from federal felony charges in that a grand jury is not required to charge a person of a crime.

Economics Teacher Beth Chase said, “I think there could be [a fault] because the grand jury only makes the decision on what they’re presented. We don’t know what they were presented that evening, and they have asked for that information to come out. Until that information comes out, we are not going to be sure that other indictments should come forth regarding that [case].”

In 2016, for example, California became the first state to ban grand juries in fatal police shootings in order for these types of cases to be transparent/open to the public in an effort to eliminate this “loophole” for law enforcement. As a result, the prosecutor determines whether to charge an officer or not.

Harvard Law Review in “Restoring Legitimacy: The Grand Jury as the Prosecutor’s Administrative Agency” vouches for transparency in grand jury proceedings, arguing that the lack thereof results in prosecutors not being held accountable: “Increased transparency would allow for voters to make better-informed decisions.”

Harvard Law Review also sheds light on the difference of grand jury proceedings in cases involving police which is likely one of the factors contributing to the low number of indictments. For example, in the case involving the death of Brown, the prosecutor allowed officers to testify in front of the grand jury.

“This disparity highlights a fundamental issue — grand jury procedures that differ based on who has been accused demonstrate arbitrariness and undermine perceptions of legitimacy,” as stated by the Harvard Law Review.

This results in increased juror bias as many trust police officers and “believe their decisions to use violence are justified, even when the evidence says otherwise.”

Rachel Petrarca (’21) said, “It is an interesting trend that they keep not getting indicted for the crimes they are committing, so it sounds like a step in the right direction, but I don’t think the root of the problem is the grand jury. I think juror bias results in such low indictments for police, especially because in their [adults] minds police are [enforces of the law], so they are less likely to want to indict those people.”

The answer is not to completely disseminate the presence of jurors in cases involving police, but rather to alter the juror’s responsibilities as to continue public involvement in this process. Jurors could make recommendations to the prosecutor regarding “charges and bargaining policies.”

Economics Teacher Beth Chase also disagrees with banning grand juries, but emphasizes the importance of presenting all evidence and information to them. She said, “I think there should be a grand jury. I think there has to be a decision made by people’s peers, but they have to have all the information. That is always the problem with the grand jury.”

In the end, it is one thing to bring a case in front of a grand jury but another to convince jurors that those viewed as symbols of law and order, rather than violence, are guilty. Thus, reform is needed within the grand jury process if society is ever to eliminate police brutality and truly achieve justice for all.