The STEM Stigma Among High School Girls

October 9, 2020

Girls can do it… right?

Thankfully, the social disparity between men and women is not as prominent today as it once was. In every societal aspect, there is a push to level the playing field between the two sexes in entertainment, sports, positions of power, and the workplace, to name a few — and to much avail. Today it’s common to see women in the Olympics. We’re not surprised to see women win Grammys, Oscars, and Emmys. But how many distinguished female scientists could you name? How many female scientists could you name at all?

There is a recognized need for girls in Science, Technology, Engineering, and Math (STEM), and there’s been many pushes to turn the tide away from the traditionally male-dominated field. Young girls now have opportunities to play with LEGO Friends sets to develop kinesthetic problem-solving skills, Goldieblox kits which explicitly promote STEM thinking to create crafts, and Engineer Barbies and astronaut American Girl Dolls who help showcase the fun of science. To further encourage participation, many high schools, Academy among them, are promoting STEM curriculum by offering Advanced Placement STEM courses, engineering courses through Project Lead the Way, opportunities for STEM internships, robotics teams, and even a STEM diploma designation, which honors students who have taken the STEM-route through their high school careers.

Nationally, girls make up half of the enrollment of STEM-related high school courses and score almost identically to boys on science and math portions of standardized tests. But despite all of this, the STEM workforce is only 28% female, with many girls dropping their STEM pursuit once they get to college; in other words, girls can keep up with boys in STEM, but they’re choosing not to. If provided the means to succeed, what’s keeping girls from pursuing STEM?

A myriad of reasons, actually — despite the deep push for girls in STEM by schools and through early development, the STEM workforce systematically perpetuates the gender gap. According to the American Association of University Women (AAUW), two of the key factors turning girls away from STEM are the gender stereotypes surrounding STEM fields, as well as the male-dominated cultures.

Did you know that only 15% of science and engineering jobs are held by women in the US? What can we do to change this statistic?

We need to teach our young women to feel comfortable pursuing a future career in STEM.#WomenInSTEM #BreakingBarriers pic.twitter.com/QACM0fiavJ

— Center for Scholars and Storytellers (@scholarsnstory) April 9, 2020

STEM fields are typically viewed as masculine, and because there are so few women in these fields, it’s difficult for girls to place themselves in an environment where they feel they don’t belong. Compared to athletics and performing arts, girls have significantly fewer role models to encourage their interest in STEM, and because STEM fields are almost entirely male, workplace cultures of exclusivity and male superiority are perpetuated and normalized, which can negatively affect the few women who do pursue STEM.

“Girls who pursue science or engineering are actively going against the masculine culture, and that can be extremely discouraging sometimes, especially if you think of how male-dominant the field has been for centuries,” said Faith Joaquin (‘21).

However, one of the most prominent reasons that girls are drawn away from science, especially high school girls, is that there is a lack of confidence in STEM-related subjects, which creates a detrimental stigma around STEM and girls who are in pursuit of it.

Compared to boys who feel confident about their proficiency in math and science as young as second grade, an overwhelming amount of girls lose confidence in their math abilities by third grade — most female teachers typically grade girls harder than boys for the same work, perpetuating the assumption that girls will need to work harder than boys to achieve the same level.

We need to continue funding girls and women in STEM because the alternative is this statistic continuing. 3 in over a century?! I just don't believe there aren't more talented women physicists out there who are capable of & busy making extraordinary contributions. https://t.co/cLUR1Y7Bgr

— anna-marie müller (@annamarie_mza) October 2, 2018

Additionally, many students who have an interest in science have likely been hurled the familiar “nerd” or “geek” insult. With the negative representation of smart characters in pop culture, as epitomized in “The Big Bang Theory” for example, girls especially regard STEM fields to be ridden with “friendless, isolated, and nerdy” scientists — and when girls are already in an environment of peer pressure, self-esteem conflicts, and the overwhelming desire to be liked, it’s no surprise that high school girls are driven away from their STEM potential by the stigma.

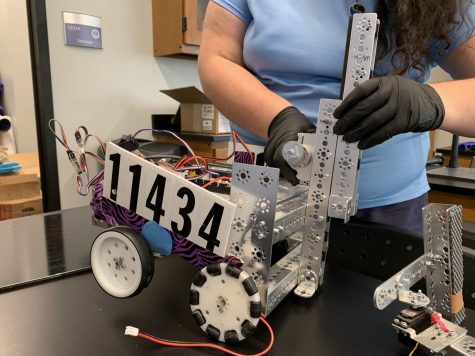

“When I decided to join robotics my junior year, my friends reacted really negatively and laughed at me, and even made fun of me. I think this was a result of the societal label that girls have as not being able to do science-related things,” said Joaquin (‘21).

While this stigma makes it hard for girls to succeed in STEM, not all are hindered by it — in fact, high school girls are more likely to take advanced science courses than boys, and make up almost 40% of students enrolled in engineering classes.

“As a student at Academy, there’s lots of ways to get involved with STEM and explore the related career paths. For example, I’ve been a part of the school robotics team for the past few years, and I’ve taken both computer science and engineering,” said Jenessa Bailey (‘21).

However, while many schools provide students with STEM opportunities, those opportunities may not be as appealing or well-developed as those of traditional female fields, like athletics or theater — and as many young girls are brought up enrolled in dance or sports, it’s difficult to spark, let alone maintain, a new interest in STEM.

“I think compared to the traditional sports or art departments, STEM programs for some schools aren’t as developed as they should be or they’re in the process of doing so. It takes a lot of work and dedication to be successful in STEM, especially for girls. I say that because, at robotics competitions, I’ve found I haven’t always been taken as seriously by my teammates who are boys. Because of that, I think it’s harder for girls to succeed sometimes,” said Olivia Scarpo (‘21).

And even when schools do provide ways for girls to be involved in STEM, the absence of frustration when catching a glimpse of the true STEM workplace isn’t guaranteed.

“Academy does a great job providing us with opportunities, but unfortunately, because women in STEM isn’t commonplace yet, sometimes I find we’re unable to compete with larger co-ed schools when it comes to robotics competitions. Other teams, who are typically all males, have at least five corporate sponsors to fund their robots. We don’t really have that, besides the budget administration gives us, and what comes out of our own wallets. It’s frustrating to think that no one wants to sponsor an all-female team,” said Bailey.

Celebrating the well deserved #women who have rightly been awarded the #NobelPrize for their development of CRISPR-Cas9, genome editing! #WomenInSTEM #WomenInScience #steminist #STEM pic.twitter.com/vqnCexnTeQ

— Jess Packard (@jepackard) October 7, 2020

In a world growing increasingly technological by the day, it’s more important than ever that girls persevere in their pursuit of STEM. Science, technology, engineering, and math each require a diversity of viewpoints for human advancement — a diversity that girls can more than provide. It’s been proven that gender-diverse teams achieve more, and make better decisions: the first airbags and speech-recognition software, each initially headed by all-male teams, did not meet success until female engineers joined the projects. Some of NASA’s most notable early feats would not be possible without female mathematician Katherine Johnson.

“It’s super important for our world that girls be involved in STEM. For us to reap the fullest benefits of innovation, we need a diversity of people designing for a diverse world. My favorite example of this is in car design: when safety features are being tested in cars, they run scenarios on one dummy that’s sized for males, and because of this, women have an outrageously higher likelihood of dying in crashes because they’re not accounted for in the design process. It’s not that the car industry has anything against women, but when everyone in a design room is male, that product will be designed for males,” said Calculus and Engineering Teacher Anne Wynn.

But to normalize women, too, changing the course of history, the STEM stigma must be eliminated, and the STEM gap between the sexes must be closed. To do so, according to the AAUW, girls must be given the skills and confidence to succeed in math and science, STEM education and support must be improved as early as kindergarten; universities must work to recruit and retain women into STEM majors, and exclusively-male cultures must be broken. But most significantly, the stigma that girls cannot like science and still be girls, must be eliminated.

“When different people and perspectives are brought together, the better the overall design will be — and to build the best possible world, we need the most diversity possible in STEM, and that begins with women,” said Wynn.