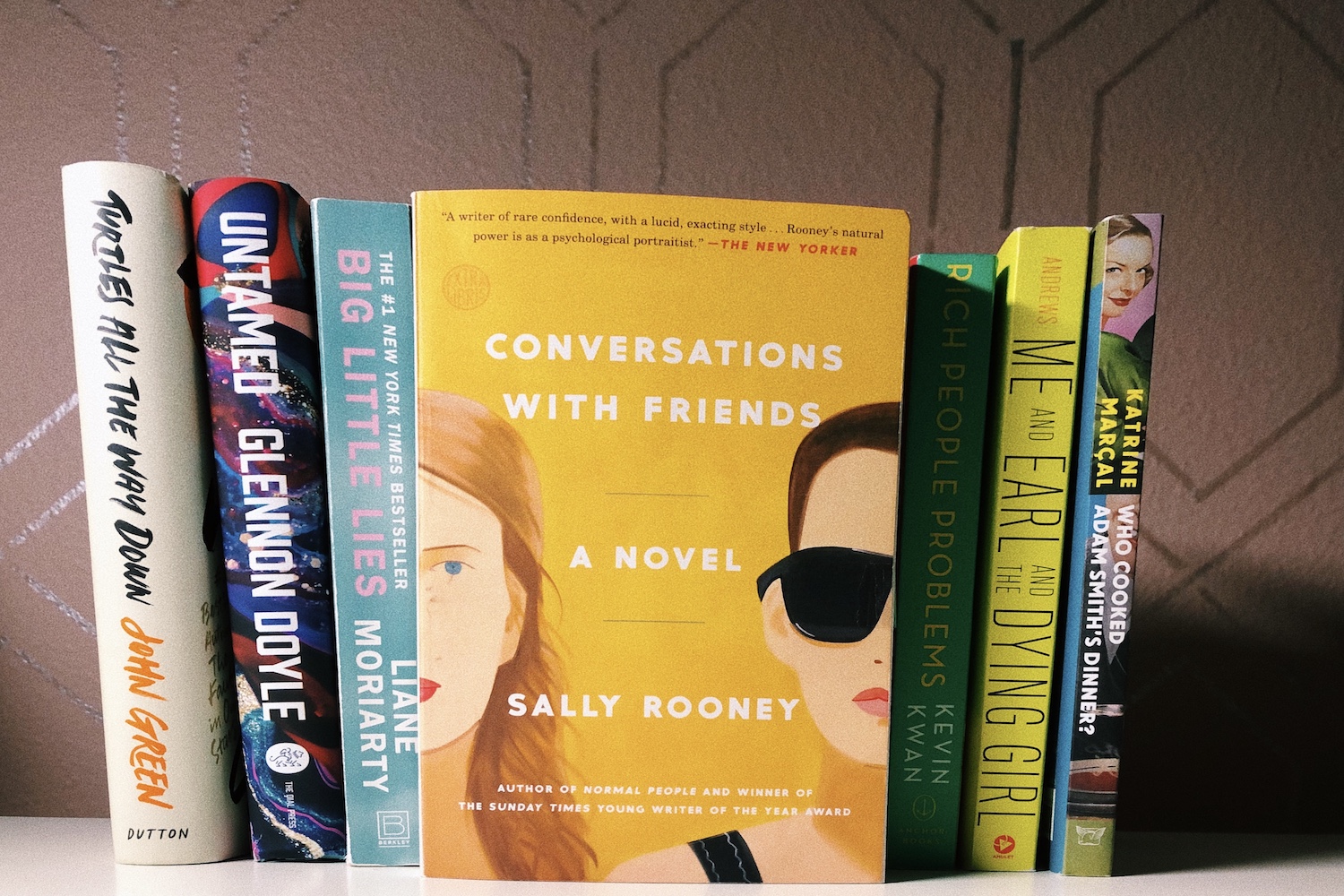

Millennial Literature: “Conversations with Friends” Review

November 2, 2020

I’d fallen in love with “Normal People” (both the novel and the televised adaptation) at the height of quarantine.

As one would expect, mandated isolation had begun to take its toll. I’d missed human intimacy and was quite keen to visually absorb Sally Rooney’s messily sincere take on young love.

Originally composed by Rooney in the August of 2018, “Normal People” had been brought to Hulu by none other than Lenny Abrahamson and Hettie Macdonald— regulars within the British film industry.

Cliché in nature, there is a je ne sais quoi to “Normal People” that one cannot help but adore. Perhaps it’s the irony of Marianne and Connell’s (Rooney’s love interests) obtuse perception of the other as they are both uncommonly bright. Or perhaps it’s, as Alexandra Schwartz so eloquently puts it, “Rooney’s natural power as a psychological portraitist.”

Enamored with Rooney’s literary technique myself, I quickly ventured to my nearest Barnes and Noble to acquire another one of her pieces.

Prior to the convoluted affair of Marianne and Connell, Rooney published “Conversations with Friends.” Much like its successor, “Conversation with Friends” is hinged upon the rather lewd flirtation between Frances, an aspiring writer attending Trinity College, and Nick, an older espoused man.

Initially innocuous, Frances is introduced to Nick through his wife Melissa, an esteemed journalist interested in profiling Frances as she and her confidant Bobbi are spoken-word poets. However, as Frances and Bobbi are drawn further into the couple’s orbit, the affair gives way to a peculiar and painful intimacy neither Frances nor Nick expect.

Sally Rooney. pic.twitter.com/bOhH9vi2s6

— Emily Ratajkowski (@emrata) April 9, 2019

I am terribly romantic, often perceiving reality in an idyllic light— hence my infatuation with Rooney’s work.

Of course, I don’t mean to suggest that she is a romanticist (she’s much too Marxist to possess such an unrealistic demeanor), but rather there is an honest idealism in shared understanding.

As we teeter along the cusp of adulthood, it is not particularly difficult to feel as if we’re indeed alone. Hormones are raging, misunderstandings are inevitable, and autonomy is just within our reach (assistance is foreign to the ordinary teenagers).

Coupled with the Coronavirus, well, the struggle is real.

Even as we regain a semblance of normality, masks continue to pose a physical barrier between human connection. A mere swath of cotton hampers in-person tête-à-tête like no other damper.

I’d found “Conversations with Friends” in the midst of my own ‘rona hysteria. Or rather, I found the alarmingly candid Frances— a character to which I felt I could relate.

Mid-musing, she reflects, “Things and people moved around me, taking positions in obscure hierarchies, participating in systems I didn’t know about and never would.”

We often pride our ability to deviate from the accepted norm, presuming ourselves to be superior as we’re more so individuals than pieces of the whole. Alas, it’s with respect to such deviations that all of mankind is inherently entwined.

Regardless of one’s communal standings, we each share the human experience— whether this be adjusting to a global pandemic or enduring the emotionally-charged years of adolescence.

Frances is most certainly not perfect, but there is beauty in her flaws, comfort in her suffering. And as a reader, I cannot help but root for her.

Perhaps Rooney’s protagonist is little more than a persona etched upon a page, yet an undeniable solace can be found in her frank navieté. Frances doesn’t have much of life figured out, but who does?

To those who have yet to read Rooney’s literature, I am so very pleased to introduce you to perhaps the first exceptional novelist of the millennium.

Please note “Conversations with Friends” contains adult themes and is intended for mature audiences.