What Does Sustainable Fashion Really Mean?

November 13, 2020

Fashion, in its eternal evolution, is never stationary, and neither is the way it’s consumed. Sixty years ago, the average American spent over ten percent of their income on clothing, purchasing fewer than 25 garments each year. Today, Americans spend less than four percent of their money on clothing –– but the average American purchases up to 70 garments per year, equating to more than one garment a week. As said by Miuccia Prada, fashion is an instant language –– but in a culture of fast fashion, overconsumption, and an ambiguous push towards sustainability, that language has become one of inescapable damage.

As boycotts of fast fashion brands grow increasingly common, Americans have begun to advocate for more sustainable methods of consumption, like thrifting or purchasing from sustainable brands. But while these environmentally-friendly alternatives seem like simple fixes, they fail to accommodate their social and economic impacts, growing the issue of ethical fashion ever larger.

America’s sizable consumption of clothing was facilitated by the rise of fast fashion –– mass-produced, poor quality, essentially “disposable” clothing sold for low prices. While many brick-and-mortar fast fashion stores have surged in popularity, like H&M, Forever 21, Zara, and Topshop, other brands like Shein, Zaful, and Romwe have gained popularity on Instagram through advertisements and celebrity endorsements.

View this post on Instagram

While the prices are low, fast fashion comes with other costs; it’s currently the second most polluting industry in the world, as the cheap, toxic dyes pollute clean water, and the “disposability” of the clothes creates 9.5 million tons of textile waste each year. Additionally, workers in fast fashion factories are provided few worker rights or protections, and are the lowest paid workers in the world.

“I think it’s very important to avoid fast fashion if possible by opting to buy thrifted clothes within the average teenager’s price point. Unfortunately, even with thrifting and doing our best to shop sustainably, it’s very difficult to do so considering the prevalence and dominance of large corporations that sell items for a cheap price because of exploited labor,” said Jehanne Caudell (‘21).

Luckily, this has not gone unnoticed –– many initiatives have been advocated for in the boycott of fast fashion, like renting clothes for parties and events or repairing damaged clothes instead of throwing them out. But the solution for buying new, inexpensive clothes without supporting fast fashion is to shop from second hand stores. Right?

It’s true that thrifting is more environmentally-sustainable than fast fashion –– but environmental focus is just one of the three pillars of sustainability. The other two, social and economic sustainability, are necessary to ensure one’s needs are met, without compromising the ability of others to meet their own needs.

“I’m a huge fan of thrift shopping. I started shopping second hand because of the low prices when I was a broke college kid, but I’ve continued to do it for sustainability reasons. Almost all of my clothes, home decor, furniture, etcetera were pre-owned. I’m very anti-fast fashion since fast fashion stores don’t pay their workers a living wage and their production is awful for the environment,” said High School Administrative Assistant Bailey Queensland.

But the issue with thrifting is that it’s not exempt from the principle of overconsumption. As thrifting has risen in popularity, an effect of advocacy from YouTubers Emma Chamberlain and Bestdressed, middle-class and upper-class consumers have rendered thrifting inaccessible for those who truly need it.

View this post on Instagram

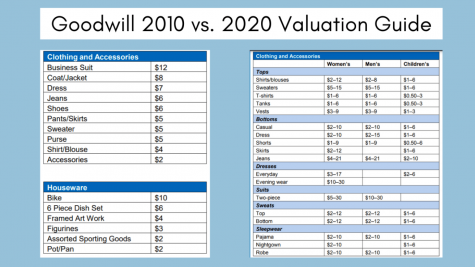

Not only have prices at Goodwill and Salvation Army risen due to demand and scarcity, but thrifting “for fun” takes clothes away from people in need –– for example, already scarce plus-sized donations are bought and tailored to fit smaller bodies, or are repurposed for their fabric.

Additionally, the trend of “thrift hauls” frequented by Chamberlain and other YouTubers promote the overconsumption of unneeded clothes –– hundreds of clothes are purchased for the video, and then never worn again. This “disposability” is no better than fast fashion.

Thrifting is both a socially and economically unsustainable solution to the dilemma of fast-fashion, as truly in-need consumers are hindered from meeting their needs. Therefore, the most proactive way to purchase clothes would be to shop from sustainable brands. Right?

Yet another conundrum within the sustainable fashion industry is that the word “sustainable” is so loosely defined. There is no true definition or measure of sustainability within the fashion world; many brands simply claim the label without recognizing the multifaceted nature of sustainability, which includes three pillars: social, economic, environmental.

“I do usually avoid fast fashion such as Shein, Fashion Nova, and Forever 21 because I believe that fast fashion is bad for the environment. I have never personally tried to shop sustainably but have considered it because of how products are made with better materials and quality,” said Alana Lopez (‘22).

To truly be considered sustainable, brands have to meet the needs of all three pillars in the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet theirs. This means that although some brands are environmentally sustainable, they might not be socially sustainable through their use of inhumane factory workers across seas. Other brands simply claim to be sustainable without providing concrete information on their manufacturing processes, as seen in 2019 with H&M’s “Conscious Collection” of allegedly environmentally-friendly clothing.

H&M claimed that their collection was more environmentally friendly than other collections, but the brand failed to provide details about their manufacturing and sourcing practices; this means that consumers couldn’t really be sure of whether H&M was truly shifting towards sustainability or simply marketing themselves in a favorable manner without substantial changes to their practices. Unfortunately, this practice is very common among low-end to mid-point fashion brands who try to appeal to consumers through deceiving marketing strategies.

This is the kind of #greenwash we get all the time as big businesses cash in on the ethical consumer, often with a slow fashion product line they run alongside their others for a wider market share…

— oakesenviron (@OakesEnviron) March 9, 2020

Greenwashing is when companies, like H&M, claim to be protecting the environment or prioritizing sustainability despite actually doing so. Lack of transparency and misleading greenwashing tactics mean it can be difficult for consumers to discern the truth regarding their favorite clothing brands.

On top of the confusion caused by greenwashing within the fashion industry, the movement towards smaller, more expensive brands within the sustainability movement is somewhat elitist. While it is true that avoiding fast fashion and cheaply manufactured clothing can benefit the planet, not all consumers can afford to change their shopping habits. The majority of fast fashion consumers have little disposable income to begin with, so it is unrealistic to ask them to pay the expensive price tag associated with truly sustainable fashion.

Elitism within the sustainable fashion industry shames low-income and middle class consumers for their choices rather than holding fast fashion brands accountable for their unethical behavior. By doing this, it discourages many consumers from participating in sustainable practices besides buying from typically expensive slow fashion brands.

“I think I’m just not accustomed to [sustainable fashion] yet; it’s just unusual for me. However, I think as it becomes more common, I’ll start shopping places and supporting small businesses. I support Thrifted Steals when they have clothes that I like, but I won’t say I’m a ‘regular,’” said Rhyan Tappan (‘21).

All i’m saying is that sustainable fashion, as it’s presented, is a privileged person’s game. Don’t shame the underprivileged for not being able to participate in it. Shame the system.

— quinta brunson (@quintabrunson) July 21, 2020

After discussing the problems of sustainable fashion, it might feel like there is nothing consumers can do about practices such as greenwashing. However, there are several actions consumers can take to improve sustainability within the fashion industry, starting with promoting brand transparency.

Advocate for clear communication from brands regarding their sourcing practices, manufacturing, pricing, and ideals. When brands mess up or greenwash, hold them accountable for their actions by boycotting.

Another way to advocate for change is by encouraging lawmakers to legislate policies regulating the fashion industry. The Environmental Protection Agency regulates industries that are dangerous to the environment, like the agriculture and oil industries, but the fashion industry is largely unregulated. While many brands manufacture overseas, there are still regulations that can be put in place in the United States to limit the environmental impact of the fashion industry.

Other practices, like avoiding over-shopping, also positively impact the environment. When possible, try to mend clothes instead of throwing them away. Most clothes that are thrown away go straight to landfills, so when getting rid of clothes, try to donate them or gift them to a friend.

When you do purchase clothes, try to do so as a conscious consumer. Apps and websites such as Good on You and the Fashion Transparency Index provide brand ratings on sustainable fashion and reward you for it. Research your favorite brands and find out exactly how sustainable they really are; as a conscious consumer, you’re more likely to make informed decisions about the brands and outcomes you choose to support.

“As individuals, the best we can do is educate ourselves on where we buy from and spread awareness on issues caused by these corporations,” said Caudell.

Try to shop slow fashion brands, or brands that encompass ethical fashion while offering versatile, timeless pieces. Buying traditional pieces that you’ll love for a long time ensures you cut down on waste while retroactively combatting the fast fashion industry. While slow fashion may be more simple, it ensures that clothes last longer than the latest trends.

Sustainability within the fashion industry needs to be enforced by consumers and brands alike, especially since the industry is the second largest polluter on Earth. Shifting to eco-friendly and humane production practices will not be easy, but it is a task consumers must hold companies accountable for if they want to see sustained, substantial change.